It’s wanting to know that makes us matter.

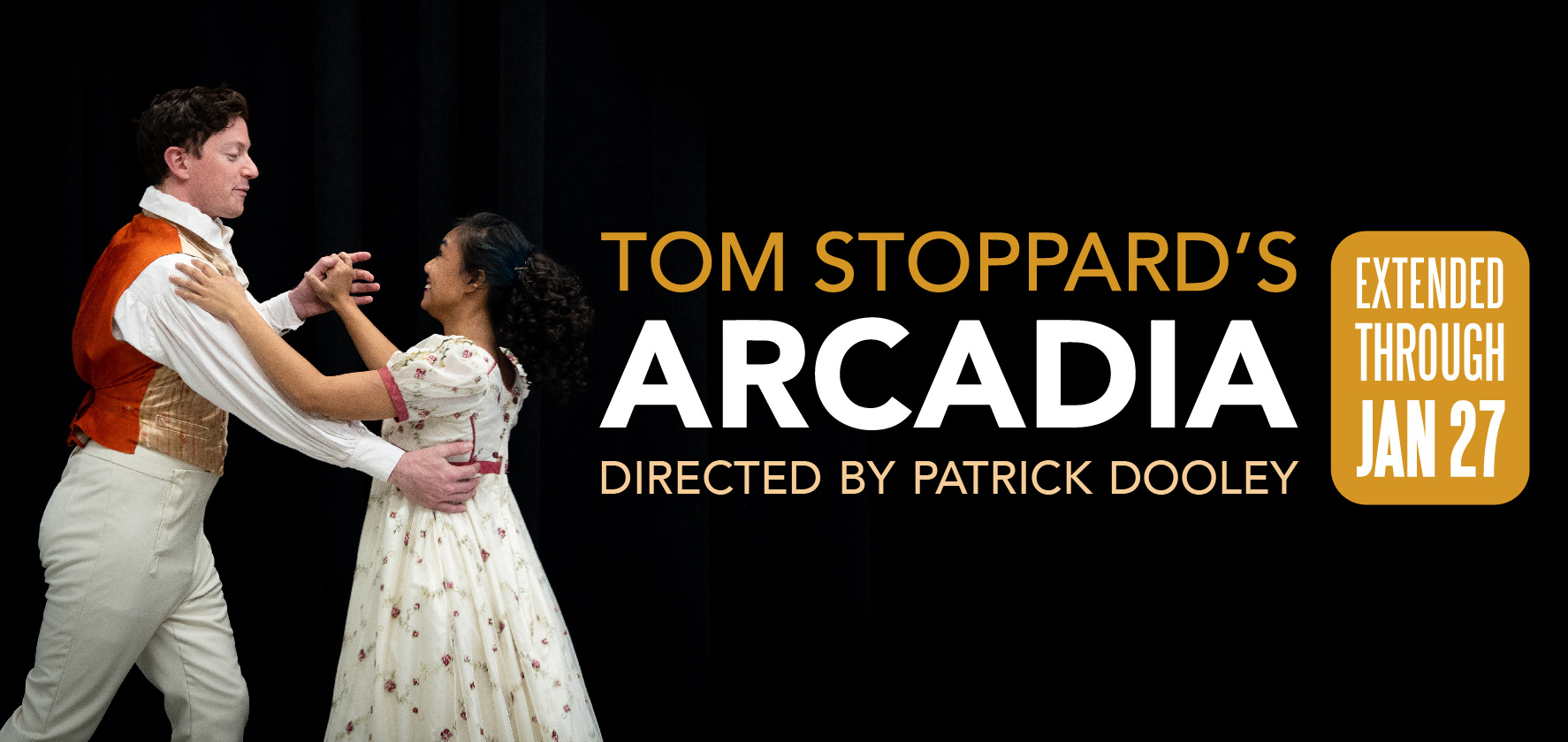

On a country estate in Derbyshire, Arcadia moves fluidly between events in 1809 and the modern inhabitants who are eager to discover what really happened in the past. We begin in 1809 where we will meet Thomasina, a teenager and mathematical prodigy, who works with her tutor Septimus. Yet we learn there are many secrets within the family on the estate. Affairs of the heart, unrequited love, and debates about chaos theory and the ideal gardening landscape flow throughout these scenes in the past. When the story moves to 1992, a garden historian and a literature professor visit to unearth the past. Was Lord Byron actually a guest? Was there a duel? Why is there a hermitage on the estate? What do the the current inhabitants of Sibley Park know about the past? Scenes move fluidly between two centuries, with an increasing reminder to cherish our time together. Arcadia is a play about passion, longing, astrophysics, and both the strength and fragility of the human heart. It’s Stoppard at his best. From the play: “Comparing what we’re looking for misses the point. It’s wanting to know that makes us matter. Otherwise we’re going out the way we came in.”

A note from dramaturg Dave Garrett

The beauty of Arcadia is that it works on a variety of levels.

On the surface, it’s a fun detective story—with slowly revealed plot points that the audience puts together just ahead of the characters as they dig through historical documents.

Beneath that, it is a playful commentary on human nature, with lost loves, jealousy, ambition, honor, and sexual repression all tossed into the mix.

Beneath that, it is an exploration—of scientific discovery in a post-Newtonian universe, of the use of mathematics to describe the world around us, and of genius and madness.

Beneath that, it is a Joycean puzzle, rich with historical allusions and oblique references—literary and otherwise. It provides fodder for cross-disciplinary theses and in-jokes between PhDs.

Arcadia’s enduring popularity is a testament Mr. Stoppard’s skill in layering these elements between two different stories taking place in 1809 and 1992.

The play itself is a testament to the spirit of discovery, and to loss and rediscovery, and getting lost along the way. And echoes of echoes of echoes.

Misplaced letters and Fermat’s last theorem. Lord Byron and the second law of thermodynamics, The history of landscape architecture and chaos theory. Forbidden love and literary scholarship. Plotting grouse populations on an x/y axis and a duel at dawn. A dwarf dahlia and the inevitability of death that awaits us all.

Oh, and carnal embrace in the gazebo. Twice.

—Dave Garrett

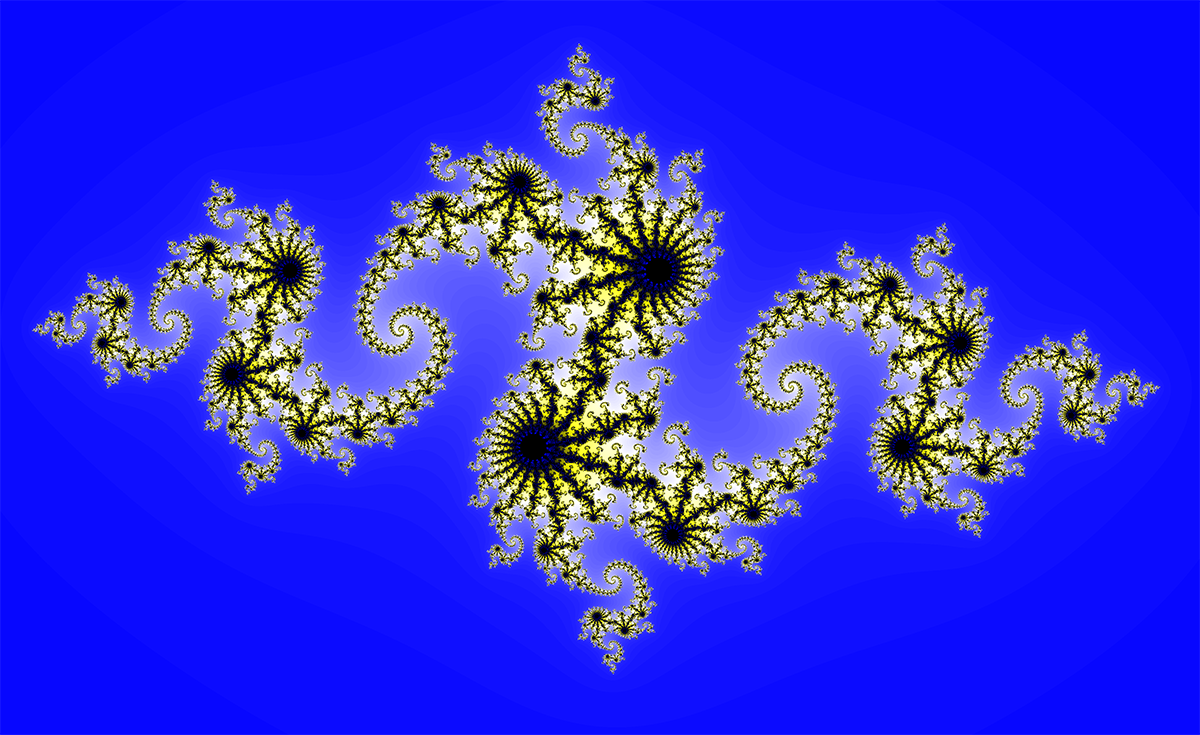

Chaos theory

Leave it to Tom Stoppard to integrate chaos theory and the revolution of mathematics so eloquently into Arcadia:

Scene 1, 1809

Thomasina:

“When you stir your rice pudding, Septimus, the spoonful of jam spreads itself round making red trails like the picture of a meteor in my astronomical atlas. But if you stir backward, the jam will not come together again. Indeed, the pudding does not notice and continues to turn pink just as before.”

Scene 4, 1992

Valentine:

“When your Thomasina was doing maths it had been the same maths for a couple of thousand years. Classical. And for a century after Thomasina. Then maths left the real world behind, just like modern art, really. Nature was classical, maths was suddenly Picassos. But now nature is having the last laugh. The freaky stuff is turning out to be the mathematics of the natural world.”

As the play unfolds, we will learn that Thomasina was a mathematical prodigy ahead of her time. Mathematics is just one lens through which Stoppard explores the complexities of human nature.

A key feature of Arcadia is that although the action of the play occurs in two different time periods, the set remains exactly the same. The objects of Septimus Hodge and Thomasina Coverly become artifacts that are researched by Hannah Jarvis, Bernard Nightingale, and Valentine Coverly—one of the heirs of the estate. Also present is the tortoise named Plautus in the 19th century and Lightning in the 20th century. Is he the sole keeper of the truth? Artistic Director Patrick Dooley comments:

“Arcadia highlights the ephemeral nature of love and life. Objects are constant, but people are inconstant—or at least inconsistent. So we kind of screw up the formula for the universe.”

Throughout Arcadia there are images of circles, and Mr. Dooley wanted to capture these images in the set design. Shotgun Players production is presented in the round, so that the audience will literally surround the action of the play. So you may want to consider seeing our production more than once—from a different perspective!

In the opening scene in 1809, Lady Croom is horrified about the changes proposed by Richard Noakes to her beloved Sibley Park:

“Where there is the familiar pastoral refinement of an Englishman’s garden, here is an eruption of gloomy forest and towering crag, of ruins where there was never a house, of water dashing against the rocks where there was neither spring nor stone…My hyacinth dell is become a haunt for hobgoblins.”

A century later (in the very next scene) Hannah Jarvis appears to agree with Lady Croom and explains nothing less than the evolution of the Enlightenment period through the landscape of Sibley Park:

“The whole Romantic sham! It’s what happened to the Enlightenment, isn’t it? A century of intellectual rigour turned in on itself…In a setting of cheap thrills and false emotion. The history of the garden says it all… the decline from thinking to feeling you see.”

Below is an excerpt from a conversation with Tom Stoppard at an Arcadia conference at the Sorbonne in 2011:

“I did have some pleasure writing Arcadia, though I am not sure that pleasure would be the word. For some months I lived in a strange, rarefied atmosphere where I didn’t talk to anybody at all. I did not know what was going to happen in the play. But naturally, normally, typically, the retrospective view of the whole play has a very powerful impulse in it which makes people want to see more planning in it than is good for a playwright.”

“It was a kind of pleasure and a form of terror because I was afraid of losing the play all the time, of hitting a brick wall. I would go to sleep thinking about it and wake up thinking about it. I just did not want to have to speak to anybody in case I lost the moment I knew I could not do without.”

What is “Arcadia” anyway? Here’s the definition dramaturg Dave Garrett shared with the cast:

Arcadia

A region of ancient Greece in the central Peloponnesus. Its inhabitants, somewhat isolated from the rest of the world, proverbially lived a simple, pastoral life. Any region offering rural simplicity and contentment. The term Arcadia is used to refer to an imaginary and paradisal place – the pagan Eden.

Et in Arcadia ego

This famous phrase also appears in Arcadia.

Contrary to what Lady Croom says, it does not mean “Here am I in Arcadia.” The literal translation, “Even in Arcadia, there am I,” came to have another meaning, where the “I” referred to death. So even in the ideal of Arcadia, death is ever present.

We look forward to seeing you at Arcadia!