|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tickets | Who's Who | Backstage | Press |

| BEHIND THE SCENES |

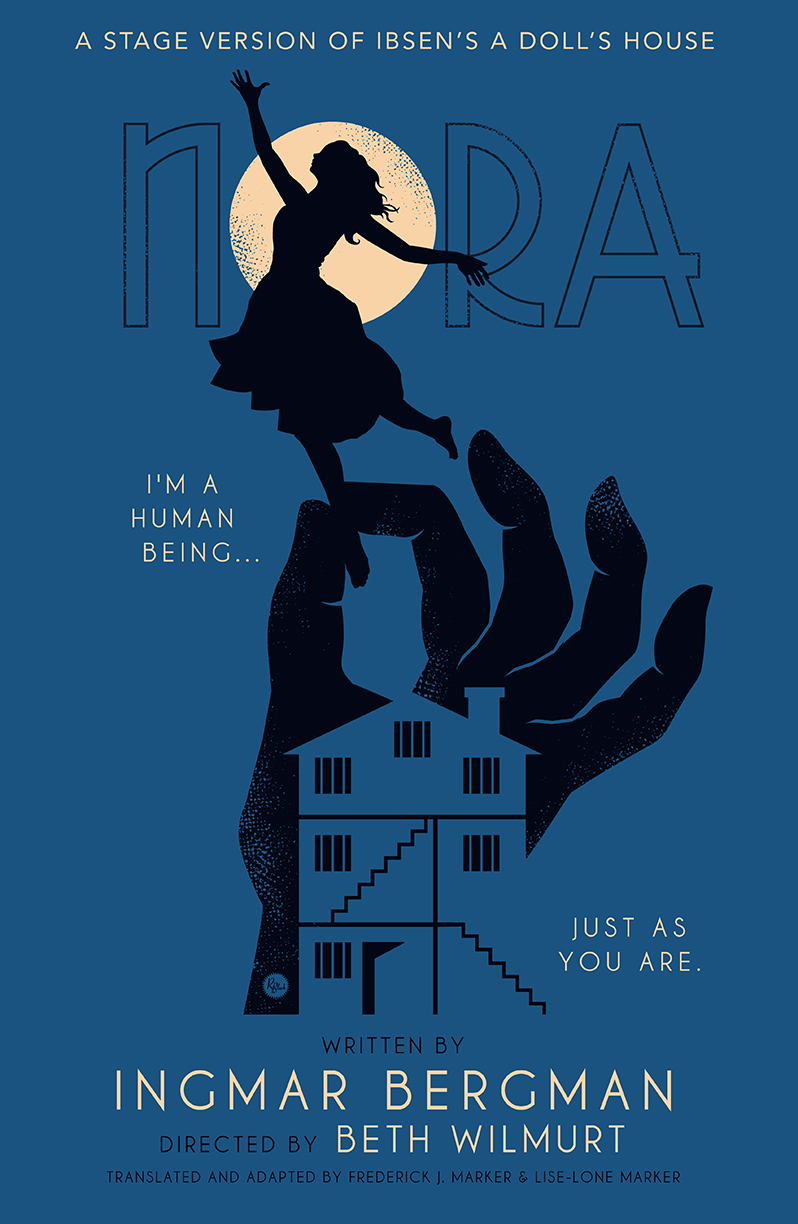

March 16 - April 16 |

|

Before the 2016 election, I assumed this was going to be a production that celebrated Hillary Clinton breaking the glass ceiling. Then overnight it became about the opposite. Many of us now feel like a stranger in our own land. And people we thought we knew are suddenly strangers too. The director Thomas Ostermeier said: “My point in making theatre is that I do not know who I am.” I read that and realized I’m doing this play, Nora, because I have a question. I want to know who I am in relation to my society. I want to become less of a stranger to myself. And I sense this play might have answers for me about how I can get to the point of action. Not prescriptions for specific actions I might take. But a process for getting at the truth of who I am, and acting on that truth. Some people say we’ve come a long way, and some say we haven’t. I’m not interested in that argument because it never ends. I’m not interested in showing oppression, a traditional interest of productions of this play. It’s too easy to denounce misogyny in a Berkeley theatre. I want to show the story of someone taking action. I want this production to encourage. “You can do it!” What will it take for me to finally take action? Why, as a woman, did I finally go on my first political march on behalf of women when I was forty-eight? What was I waiting for? What was I afraid of? What did I miss? Nora is someone trying to figure out who she is. She’s testing things. Trying things. She doesn’t know where she is on her journey but she senses an impending crossroads. Maybe you do too. Maybe you did on November 8, 2016. Maybe now we’re all finally awake and, bleary-eyed, figuring out how to stand and walk. —Beth Wilmurt

The Story

Do you ever really know your partner until a crisis unfolds? When the curtain is pulled back to reveal Nora and Torvald’s true power dynamic, their marriage is put to the test. In the recent words of Mitch McConnell, “she persisted.” Nora is a story that delves into gender dynamics, deceit, and the courage it takes to make unconventional choices. The patriarchy inherent in our “modern” 21st century still begs to be dismantled, and Bergman’s adaptation shows Ibsen to be as revolutionary today as he was in 1879.

Ingmar Bergman, 1966 Ingmar Bergman created his streamlined version of A Doll’s House in 1981 to be presented along with his adaptation of Strindberg’s Miss Julie. Ibsen’s original script includes a nanny, a maid, a messenger, two children. Bergman streamlines his adaptation so that the focus is upon the five lead characters: Nora, Torvald, Krogstad, Christine Linde, and Dr. Rank. Bergman entitled his adaptation Nora and wrote that the characters are "caught in private hells of their own devising, trapped in relationships that are defined and deformed by a litany of recurrent rituals.” Director Beth Wilmurt read several versions of A Doll’s House. Finally, she put the test to the cast. They gathered at artistic director Patrick Dooley’s home and read two versions of the script in one day—including Bergman’s Nora. It was unanimous! Everyone preferred Bergman’s version of the play. He streamlines the action of the play so that the focus is upon the relationship—or lack thereof—between the central characters. Bergman also makes some intriguing changes to the original tale. If you think you know the play, prepare for a few surprises when you come to the Ashby Stage.

The Happy Ending When A Doll’s House debuted in 1879 there were several positive reviews but without question there were many who found the ending of the play highly controversial. In 1880, a theatre in Germany wished to produce the play, but the actress who was to play Nora was offended by the ending. Apparently she said: “I would NEVER leave MY children.” Since his play was not copyrighted in Germany, Ibsen decided to write an alternative ending. He wrote the following explanation to a Danish newspaper: Immediately after the publication of A Doll’s House I received a communication from my translator and agent for the North-German theatres, saying he had reason to fear the publication of another translation or adaptation of the play with an altered ending, and that this would probably be preferred by a considerable number of North-German theatres. In order to prevent this eventuality I sent my translator and agent the draft of an alteration to be used in case of necessity. In this version Nora does not leave the house. Instead, Helmer forces her into the doorway of the sleeping children’s nursery, the parents exchange a few lines, Nora sinks to the floor and the curtain falls. I have myself described this alteration to my translator as a barbaric act of violence towards the play. Its use is absolutely contrary to my wishes, and I hope that it will not be used by many German theatres. Below is the alternate ending that Ibsen created:

HELMER. Go then! [Seizes her arm.] But first you shall see your children for the last time! NORA. Let me go! I will not see them! I cannot! HELMER [draws her over to the door, left]. You shall see them. [Opens the door and says softly.] Look, there they are asleep, peaceful and carefree. Tomorrow, when they wake up and call for their mother, they will be - motherless.

NORA. [trembling]. Motherless...! HELMER. As you once were. NORA. Motherless! [Struggles with herself, lets her travelling bag fall, and says.] Oh, this is a sin against myself, but I cannot leave them. [Half sinks down by the door.] HELMER. [joyfully, but softly]. Nora! [The curtain falls.]

Ibsen’s Source Henrik Ibsen had a friend named Laura Kieler who approached him for a loan. Her husband had tuberculosis and she needed funds for a cure. Ibsen was unable to help her—so she arranged for an illegal loan for the medical expenses. When her husband learned about her actions, he not only divorced her, he had her committed to an asylum for two years. Ultimately, the couple reunited and Laura Kieler later became a successful author. Some scholars have argued that Ibsen was driven to write A Doll’s House partially out of guilt for not having provided a loan. Yet he created an unconventional heroine who still resonates strongly for us today. |