|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tickets | Who's Who | Backstage | Press |

| Reviews |

March 16 – April 16 |

"Wilmurt makes a familiar world bewitchingly strange." —Lily Janiak, San Francisco Chronicle "Wonderfully taut" —Jean Schiffman, San Francisco Examiner "An attractive production" —Emily S. Mendel, Berkeleyside "A performance to be long remembered" —Eddie Reynolds, Theatre Eddys "Do we need to see these old war horses whose mores are so passé? The answer is yes." —Victor Cordell, For All Events "A concise, 5-character quasi-thriller with a relentless forward thrust and no extra fat left on the bone." —Mark Johnson, Theatre Arts Daily "A brilliant work" —Jeremy Geist, Bay AreaTheatre and Bites

PRESS RELEASE (PDF)

|

Shotgun’s pared-down Ibsen has fewer words, more power

by Lily Janiak | March 26, 2017

San Francisco Chronicle

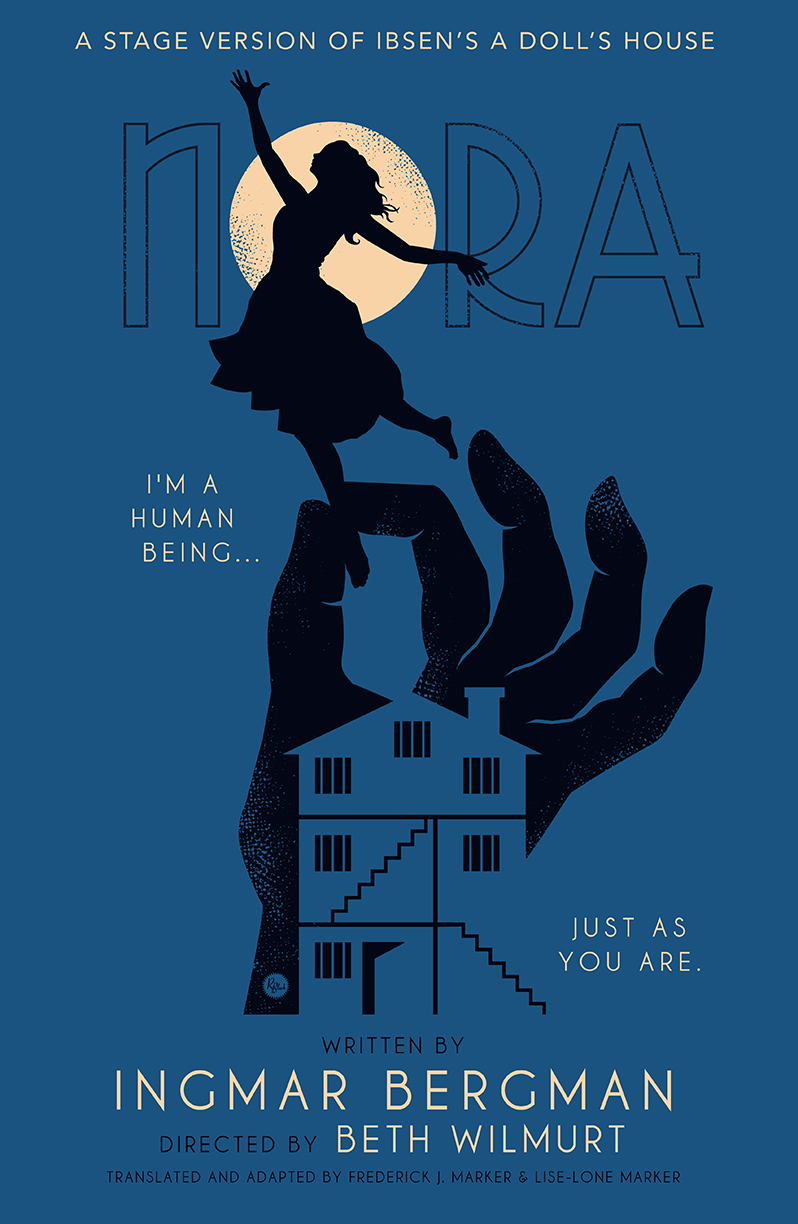

Less is, if not more, at least freshly emphatic in the economical version of “A Doll’s House” retitled “Nora” and seen Friday, March 24, at Shotgun Players’ Ashby Stage.

Ingmar Bergman has stripped away all the minor characters of Henrik Ibsen’s classic, and pared away so much exposition that the three-act drama almost flies by in an hour and 40 minutes without intermission. Bergman’s “Nora” paints a stark portrait of a marriage as a series of transactions, with no need for all the times Torvald calls his wife a “squirrel” to make its point.

Bergman’s adaptation gives fresh emphasis to the original play’s shrewdest point: In a society built on inequality, relationships lose their humanity. If, as a wife, you must always bargain with your husband, whose dominant role in the marriage is enforced by your community, you are condemned to live not in a marriage, but in enslavement.

Directed by Beth Wilmurt, “Nora” refreshes the 1879 proto-feminist classic in still other ways. Even if you’ve seen “A Doll’s House” before, you’ll likely find yourself convinced characters will choose differently this time.

Wilmurt makes a familiar world bewitchingly strange. You might feel that instead of experiencing one of the foundational stories of modern drama, one that helped lead theater out of melodrama and into realism, you’re watching something new and experimental. How else to explain the way each character seems desperate to divulge a shameful secret; lay bare a forbidden desire or childish fantasy; enumerate, with disarming candor, each of his or her social and financial privileges — exactly the sort of thing society schools one to conceal?

In the case of Nora (Jessma Evans), it isn’t even a trusted confidante she tells all to, but a school friend she hasn’t seen in about a decade. Christine Linde is played so gravely by Erin Mei-Ling Stuart that each plea about a pitiable lot in life registers with battalion force. This newcomer goes from darkening Nora’s door (except there’s no front door in Maya Linke’s smart, open set, leaving Nora to labor at her delusions sans protection, in full view of many judges) to hearing all the sordid details of Nora’s wheelings and dealings, her selfless but nonetheless shady attempts to secure the health, fortune and reputation of her husband Torvald (Kevin Kemp).

So often, productions of Ibsen get mired in their ponderous exposition, but under Wilmurt’s direction, characters utter each thought, no matter how seemingly banal, no matter how in service to back story, as if it might be their last. In a breakout performance, Evans limns each line reading with so much earnest yearning to maintain a false front, yet so much deathly fear of the cracks in her facade, that exchanges about wills and contracts take on the very weight of the universe. From breath to breath, she seems to at once persevere mightily, with a generous if tearful smile ready for whomever should next cross her porous threshold, yet also to buckle, to yield before others more sure in their own personhood.

Contemporary productions and adaptations of “A Doll’s House” often fail to make Torvald more than an easy villain, a chauvinist his audience is all to ready to denounce. Shotgun’s “Nora” doesn’t solve that problem — partly because the cuts don’t give us time to fully register the play’s emotional peaks and troughs, partly because of Kemp’s magisterial, even mechanical, delivery. That means Nora’s climactic decision doesn’t reverberate with society-rending force. But in Evans’ rendering, it still chills.

Lily Janiak is The San Francisco Chronicle’s theater critic. Email: ljaniak@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @LilyJaniak

Fast-paced ‘Nora’ updates Ibsen for 21st century

By Jean Schiffman | March 26, 2017

San Francisco Examiner

First produced in 1879, Swedish dramatist Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House” — in which a young wife and mother finds her own inner strength in the face of a domineering husband and oppressive society — still resonates with audiences.

Ingmar Bergman’s stage version, “Nora,” streamlined to focus on the five principal characters, suits our fast-paced times with its whirlwind plot and its characters’ rapid attitude adjustments.

The dizzying pace places quite a burden on the actors: They must absorb and respond to shocking changes of circumstance in the course of an hour and 40 minutes in Shotgun Players’ minimalist, intermission-less staging.

Without her husband Torvald’s knowledge, Nora, viewed as a charming child (a “doll” by Torvald) has borrowed money from Krogstad, an unscrupulous colleague of Torvald’s. That money was necessary to save Torvald from a health crisis.

Now Nora is secretly repaying the loan.

But things quickly spiral out of control when Krogstad blackmails Nora. Also in the mix are the couple’s close friend Dr. Rank, and an old schoolmate of Nora’s with pressing needs of her own.

Among director Beth Wilmurt’s intriguing expressionist choices: The main action is on an almost bare platform (set by Maya Linke) emanating from a back wall with a sliding door in it; the wallpaper is an unnerving pattern of black and white illustrations of women’s faces, and the wall itself advances and recedes at a few well-chosen, starkly dramatic moments.

Characters tend to come and go from a shadowy periphery. And, in this period piece, only Nora — she who must break free of traditional mores by play’s end — wears modern slacks.

The staging is wonderfully taut: Actors move in clearly defined, economically precise patterns and are often unnaturally stationary, reflecting their constrained environment. On opening night, though, some cast members had not yet made that precision organic.

In addition, in an uneven cast, there are some wooden line deliveries and thin characterizations.

As the heroine who morphs from childlike impulsivity to steely-eyed self-confidence, Jessma Evans is impressive. She’s an open-faced Nora whose thought processes are beautifully transparent even as she masks them from her husband, and whose perfectly paced evolution is utterly convincing. In the final scene, as she hovers outside the playing area, she actually looks physically different, her face, so round and cherubic in the first scene, now calm and sculpted.

Nora

Eddie Reynolds | March 25, 2017

Theatre Eddys

When Ibsen premiered A Doll’s House in 1879, controversy immediately erupted when his banker’s wife and mother of three challenges the society’s definition of marriage and walks defiantly away from hers, seeking to discover who she really is beyond those two, domestic titles. At the time, Ibsen said he was inspired by the prevailing belief that “a woman cannot be herself in modern society” because [society is] “an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint” (italics added).

It is that final part of Ibsen’s statement that makes Shotgun Players’ current production of Nora – Ingmar Bergman’s 1988, pared-down version of Ibsen’s original – so timely, in a very unfortunate way. After seeing the manner the most prepared candidate ever running for U.S. president (who happened to be a woman) was treated and compared by both press and public as opposed to the way was the least-ever prepared candidate and to-be winner (of course, a man), Ibsen’s statement and reason for writing his play now feels more relevant than ever – a sad commentary 125 years later and after women supposedly won their full rights long ago. Shotgun Players presents a compelling portrait of a woman who transforms before our eyes, becoming a pillar of confidence and determination – a metamorphosis emanating from a decision bold and justified but a decision all others around her deem inappropriate in every respect, all because she is a woman. And while we watch wanting to see the play as an interesting museum piece, we slowly realize that the play actually mirrors attitudes still too dominant in our current world.

Nora is a woman who holds a secret she describes as “the source of my pride and joy.” She is slowly, meticulously paying back a sizable loan she covertly made three years prior to save the life of her husband -- Torvald, now a banking manager – in order to send him to a warmer client to recover from a debilitating condition. To obtain the loan as a woman, she forged her dying father’s name – an act of love now threatening her seemingly perfect life. Nils Krogstad, the source of her surreptitious loan, is now about to be fired by her husband and promises to reveal her crime of forgery to all the world (especially her straight-and-narrow, patriarchal husband) unless she can convince her husband to reverse the planned action. But in a world where a wife’s place is in a “play room” as her husband’s “doll thing,” influencing her husband to reverse an act he has already made public leads him to only one conclusion. “I would lose face,” he says appalled at the thought of doing what she want – an outcome worse than death in his world of total machismo.

The magnetic pull is overwhelming to keep our eyes locked on Jessma Evans as she portrays Nora and ignore all else. With high, full cheeks that call attention to mischievous dimples and sparkling eyes, her beginning persona can be totally believed as she declares, “It is truly wonderful to be alive.” How proud she is to tell her shocked and skeptical childhood friend, Kristine Linde, about the secret loan and the things she has done since to make money to pay it off. “So fun ... making money ... almost like being a man,” she reveals with confident accomplishment broadcasting from her being in every way Ms. Evans can possibly muster.

But as the threats of her loan shark come to fruition and reactions mount against her, her light-hearted Nora transforms to someone almost not recognizable, yet increasingly more real and admirable. There is a transition period as she is slowly taking in the changes occurring around her when her countenance becomes frozen -- eyes not moving and mouth slightly open, not speaking. As the realization becomes evidently clear to her that she is no longer who she once was and now must take the step to see who she now is, dramatic shifts in her persona occur. It is as if a different actress has stepped into the role of Nora, so dramatic are those alterations of voice, stance, and manner. In a performance to be long remembered, Jessma Evans becomes every woman -- every person -- who has suddenly had that epiphanic moment of a life-changing decision that feels so sure, even when there is no supportive confirmation offered from anyone around her.

Surrounding Nora in this journey she did not wish upon herself are people whose relationships with her and each other are defined by a tangled web of ill-conceived and/or ill-received decisions made under male-dominated, societal norms. Childhood friend and now-widow, Kristine Linde, suddenly reappears with secrets and an air of mystery that Erin Mei-Ling Stuart emulates through her dark, hovering presence countered by an air of genuine concern (but not approval) she bestows on Nora’s revelation about the loan and the resulting blackmail. With a set jaw and eyes that have clearly endured suffering, Kristine is a woman strong in nature and resolve in her own right but who still operates within the boundaries of societal dictates – boundaries she hopes to pull Nora back safely within.

Michael J. Asberry is Dr. Rank, a wealthy and close family friend of Torvald and Nora. Now near death, the congenial, gracious, and dignified Doctor with a voice deep, smooth, and soothing is ready to reveal some secrets of his own before passing out of Nora’s life – revelations whose reception shows even Nora still carries her own deep-set, societal do’s and don’ts just as she is about to reject those that are entrapping her.

Bearing down on Nora face-to-face in his demands and threats, Adam Elder’s Nils Krogstad is absolutely demonic in a desperate, yet still pitiful manner as he seeks reinstatement into his job at the bank. The stalking, weasel part of Nils is however not the whole of who this man is. Mr. Elder is masterful in gradually revealing a much more nuanced, complex man – one who has made his own tough choices for another’s well-being and one who has had his own share of disappointments.

On the one hand, all-adoring of Nora but on the other, all-controlling of her and suffocating any attempts she makes toward independent, self-expression, Torvald is dripping in his handsome charm while also over-flowing in ego-and-male-centric attitudes. The result is that he continually boxes his wife into an ever-collapsing definition of who she is allowed to be (well illustrated in Maya Linke’s set design and a stage that becomes ever smaller with an approaching and thus threatening back wall). A role written with much, rich potential in its attract/avoid range of possibilities, Kevin Kemp is unfortunately too one dimensional in his approach to Torvald, over relying on a constantly loud, cymbal-like, and almost stomping approach in delivering his lines (and then too often stumbling in their delivery, at least on the night I happened to see him).

Director Beth Wilmurt and her creative team warn us in a number of clues that there are winds of change, probably not good ones, coming into Nora’s life. In a heavy, black cloak of mourning (costumes by Maggie Whitaker), Kristine is the first person we see and one who lingers long on the sidelines with foreboding side glances before entering Nora’s house. A low, uneasy, and moaning set of notes is heard somewhere in the distant and barely discernable background as part of Matt Stines overall outstanding sound design. Already mentioned is the wall papered with women’s silhouetted heads (as if paper dolls) that moves ever slowly as Nora’s chances of happiness in this same house become ever fewer. Even the seemingly awkward manners that set pieces are moved in and out of the one door in the wall are done in ways that seem to illustrate how difficult it is to shift anything anchored firmly in this society’s landscape.

Pared down from Ibsen’s three acts to one long act (one hour, forty-five minutes), Shotgun Players’ version of Ingmar Bergman’s Nora moves in a well-paced, no-exit manner toward a decision that today still feels unnatural and unsettling yet at the same time, justified and triumphant. The real unease upon leaving is how long will it take until a generation watching this nineteenth-century story will see it as a piece of long-ago history and not still a part of current reality.

Shotgun Players does ‘Nora:’ Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’ as revised by Ingmar Bergman

Emily S. Mendel | March 27, 2017

Berkeleyside

Shotgun Players is always ready to try the off-beat or difficult play. It never insults its audience with the mundane or prosaic. So, one can see why Shotgun found Ingmar Bergman’s 1981 stage version of Henrik Ibsen’s immortal 1879 A Doll’s House such an attractive production. And an attractive production it is. With Jessma Evans (Top Girls) excelling as Nora Helmer, and Kevin Kemp as her husband, Torvald, there is lots of life left in Ibsen’s 138-year old creation — with a few tweaks by Bergman.

Ibsen’s original script, in which the infantilized Nora finally awakens to her second-class status and walks out on her paternalistic, self-righteous husband and their children, was shocking to society when it was first produced, although now it is all too commonplace a domestic scene. Yet it can still be moving to observe Nora experiencing abandonment instead of adoration in her husband’s attitude, as she becomes aware of the meaningless and artificiality of her life.

Bergman’s script (translated and adapted by Frederick J. Marker and Lise-Lone Marker), does not dramatically alter A Doll’s House. Rather, it eliminates several characters, including servants and children, and tones down some of the more archaic language and pet names Torvald called Nora in the original version. But it is still interspersed with stilted dialogue that caused occasional, inappropriate laughter by members of the audience.

Bergman moderated Torvald’s archness by making him a bit more human, but Torvald still doesn’t get Nora at all. Bergman said in 1981, I see [Torvald] Helmer as a very nice guy, very responsible. [The play] is really the tragedy of [Torvald] Helmer. Bergman may see Torvald’s tragedy as his inability to treat his wife any differently than his society dictated. But to most audiences, the tragedy is Nora’s. After all, Ibsen based his drama on the experiences of a woman he knew.

Beth Wilmurt, a gifted actor on the Ashby Stage (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), seems more accomplished at directing than one might think, knowing Nora was only her second turn at bat. She has concentrated on adding more action to the drama, and even included a suggestive sexual interlude between the Helmers.

However, at times the staging of Nora seemed to get in the way of the acting. Without any servants, Torvald’s faithful companion, Dr. Rank (Michael J. Asberry), Nora’s childhood friend, Mrs. Kristine Linde (Erin Mei-Ling Stuart) and the blackmailer, Nils Krogstad (Adam Elder) wander on and off the stage, appearing inside the Helmer house as if by magic. This problem is exacerbated by the Ashby Stage’s high platform/stage, which has no steps to aid entrances and exits. And perhaps there is deep meaning that I missed in why Nora pushed the heavy sofa on to the stage at the start of the play and a table and chairs later on, and why the well-chosen wallpapered backdrop moved forward and backwards during the performance.

Bergman didn’t omit any of the key elements of A Doll’s House, and his starker version focuses the drama. But the play is still dated, although not old enough to be appreciated as a timeless tragedy. Nevertheless, it’s an interesting production, presenting a fine opportunity to see Ingmar Bergman’s homage to Henrik Ibsen’s masterpiece.

Nora

by Victor Cordell | March 25, 2017

For All Events

A house is not a home.

“Nora, you are first a wife and mother.” “No, Torvald, I am first a human being.” Such is the essence of conflict in Henrik Ibsen’s classic play A Doll’s House . Conventional thinking in late 19th century Norway and most other societies would have supported Torvald’s position, that a woman’s responsibilities are domestic and that her stature is reflective as indicated by the successes of her husband and children. Though Ibsen denied consciously taking up the banner of woman’s rights, the nature of Nora’s crisis was unique to women. With or without intent, he created a seminal heroine for the movement.

The great Swedish cinema auteur, Ingmar Bergman, took it upon himself to improve on one of the world’s greatest playwrights, and created Nora , based on Ibsen’s work. In large measure, he condensed A Doll’s House by eliminating characters and subplots. What remains is a thoughtful rendering of the central theme, which stands on its own and meets the modern sensibilities of our more hurried existence. As such, Shotgun Players should satisfy a younger audience and those unfamiliar with the original work. Those who know A Doll’s House will find an interesting contrast and have the pleasure of debating the merits of this manner of adaptation.

The setup of the storyline is quite simple. A typical married woman, Nora is enthused at husband Torvald’s promotion to manager at the local bank, and she has gone on a spending spree well in advance of money to pay for the extravagance. Meanwhile, an employee of the bank with a dark past, Krogstad, has learned that he is about to be fired. He secretly implores Nora to intervene with Torvald. What connects Krogstad and Nora so that she might be inclined to help him? He had secretly lent her money in order that she and Torvald could spend time in Italy for him to recover from an illness. Torvald was not aware of the relationship, and its revelation could be quite damaging to his career and standing in the community.

Director Beth Wilmurt has utilized spare sets, usually with only a settee or a table and two chairs on the stage, focusing the attention on the actors. Leading up to the point of conflict, the figurative first act (there is no intermission) is interpreted in a somewhat comic manner. It is interesting to listen to lines delivered in light hearted fashion that one is accustomed to hearing in the stolid Scandinavian style.

Although the other main characters wear period dress, the trousered Nora’s is of a more modern ilk, suggesting that the others are in concert with tradition, while Nora is pulling forward. As Nora, Jessma Evans offers a naturalistic performance and is comfortable in the modern idiom of her dialogue. Her glibness, however, belies concerns that are later revealed. Kevin Kemp’s affect as Torvald is somewhat updated, but the actor still adeptly conveys the stiff-necked propriety and male condescension of earlier times. Adam Elder convinces as the swarthy and menacing Krogstad, his visage sheltered by a pulled-down hat. Michael J. Asberry provides a comforting presence as the affable family friend, Dr. Rank, while Erin Mei-Ling Stuart conveys a sense of mystery as Kristine, the widow who has returned home after living away.

It is interesting that clusters of the same or related works often appear in the same season around the Bay Area, and it is a shame that few theater goers are alerted to the possibility to witness and compare them, or that the producing companies don’t seize the opportunity for joint marketing. For instance, three worthy variations of the Antigone theme appeared two years ago, one of them by Shotgun Players. Three Othellos appeared last year. This season, Nora was preceded by Cutting Ball Theater’s adaptation and update of Hedda Gabler , Ibsen’s other groundbreaking leading lady. In addition to the two productions being of individual interest, the divergence of character between the two profound exemplars deepens the insight into the society from which they come. Nora has been the model wife, attentive and sacrificing, while Hedda is self-indulgent and scheming.

Of course, the question remains – do we need to see these old war horses whose mores are so passé? The answer is yes. Not only do they provide lessons of history, but it should be clear that some of the vast changes that we collectively embrace are neither uniformly adopted within societies nor universally adopted among societies.

Review: “Nora” at Shotgun Players

Mark Johnson | March 27, 2017

Theatre Arts Daily

It appears that 2017 is the year of cut-down Ibsen productions in the Bay Area. First, you had the Cutting Ball’s 75-minute edition of Hedda Gabler, of which the less said the better, and now Shotgun Players is staging a production of Nora, a version of A Doll’s House written by Ingmar Bergman (of The Seventh Seal and Persona) that lasts 95 intermission-free minutes. Unlike Hedda Gabler, however, this Nora is a winner, a fully engaging evening of theatre, sparse-yet-effective, and currently being produced in Berkeley in a top-notch staging until April 16th.

A Doll’s House is considered to be one of the foremost European dramas of the 19th century. Premiering in 1879, it shocked audiences around the world thanks to a twist ending that featured Nora, a housewife and mother, realizing her ultimate unhappiness in her societal position as a woman and deciding to pack her things and get the hell out of her current life to go in search of herself. Women in domestic dramas at the time were typically given the ultimate fate of either shooting themselves or returning back to their lives, content with where they are. The idea that a woman could find happiness and find it without her presupposed societal role was a radical one at the time—radical enough for the work to be considered a landmark of nascent feminist literature.

Ingmar Bergman, who prepared this version of A Doll’s House to be performed in repertory with his adaptation of Miss Julie and the stage version Scenes From a Marriage, saw the work less as an example of feminine liberation and more as “the tragedy of [Torvald] Helmer…he’s a decent man who is trapped in his role of being a man”. This is visible in his cutting down of the text, which excises almost half of the written material, and in which Torvald is presented far more sympathetically than he usually is, with much (though not all) of his condescending nicknames and what the millennial argot might refer to as “mansplaining” removed to create an overall less antagonistic character.

The changes create a final scene in which Nora’s decision is shown to cause far more pain than in Ibsen’s original, and though Nora’s leaving is still ultimately the right choice for herself, it’s less inspiring and more tragic. Bergman thus repurposes Ibsen’s central message to be less “humans must liberate themselves from toxic societal structures to find happiness” and more “humans must liberate themselves from toxic societal structures to find happiness, no matter what the cost”.

This might be a more potent message, but it’s a less satisfying conclusion, and Bergman’s adaptation makes one miss Ibsen’s formal cushiness, in which he allowed all events more than their fair share to breathe. One can’t help but feel that the proceedings are a little cramped when stuffed into such a tight space. Thankfully, Bergman was no dramaturgical slouch, and he managed to turn A Doll’s House into a concise, 5-character quasi-thriller with a relentless forward thrust and no extra fat left on the bone. Those familiar with the Ibsen original will wish that they were watching the Ibsen original, but for newcomers, Nora is short enough to be palatable and gets the point across well-enough. Frederick J. and Lisa-Lone Marker’s translation starts off rather uncomfortably foreign-sounding, but quickly picks up steam and hits the bullseye by the time the play reaches its climax.

Shotgun Players is one of the best companies in the region, and the chance to get to see such top-notch productions where the actors are close enough to touch is a uniquely thrilling opportunity. Nora is exactly in line with what audiences would come to expect from Shotgun Players, which is to say that the production could hardly be bettered. Beth Wilmurt, the director, is one of the finest actors around (she gave what I might consider to be the definitive performance of Martha in Shotgun’s own Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? last year) and, as one might expect, she gets performances of an extremely high caliber from every member of her 5-person cast. I was also pleasantly surprised at her ability to stage physical action, with her visual sensibilities running towards images of symmetry and her actors always in constant cycles of tension and release with each other. I would say that I look forward to more plays staged by her in the future if I weren’t so damn eager to see her back onstage as an actor.

As previously mentioned, the cast is all-around excellent. Nora Helmer is one of the great roles of the western theatre, and Jessma Evans is more than up for the challenge. Her performance is one of constant and gorgeous awkwardness, always unsure of what to do with her body, before finding her grounding in the final scene. It’s mesmerizing to watch, and marks her as an actress to watch in the coming years. If any company is planning on producing The Seagull and hasn’t found their Nina yet, I think I might have found her for you. Michael J. Asberry is wonderful as Dr. Rank, with his booming baritone voice perfect for the character’s ruminating on the nature of mortality. Also of note is Erin Mei-Ling Stuart, who plays Mrs. Linde, Nora’s childhood friend, and gives an anti-performance of remarkable conviction that works surprisingly well. The physical production is most impressive, with Maya Linke’s beautiful and expressionistic set contributing to a coup de théâtre that makes as much dramatic sense as it does dazzle the audience.

I wish that every element of this production, the cast, the director, the set, were for a production of A Doll’s House rather than Bergman’s Nora, but that does not mean that this Nora is not a thoroughly satisfying and intellectually invigorating evening of theatre. It’s doubtful that a better production of Ibsen will be seen in the Bay Area this decade.

Shotgun Players: Nora

Jeremy Geist | March 27, 2017

Bay Area Theatre and Bites

In 1879, shocked audiences watched Nora leave her husband to pursue an education at the end of the first production of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Since then, the play’s feminist themes and complex relationships have elevated it into the pantheon of modern dramatic masterpieces. But it’s not Ibsen’s version of A Doll’s House that Shotgun Players has chosen to start off their season – rather, it’s the theatrical adaptation by legendary film director Ingmar Bergman (The Seventh Seal). The adapted script, along with Shotgun’s fascinating artistic decisions, cut away the chaff from the original to create a lean, tense experience.

Shotgun’s smartest move was not underestimating their audience; Nora is especially rich for theatregoers familiar with Ibsen’s original work. Although the basic story beats are the same, the production moves away from familial drama and into a character study of Nora herself, as she becomes increasingly pressured by a patriarchal society. Jessma Evans creates a nuanced view of the character: She takes lines that would normally indicate subservience and reinterprets them into strikes at the people who continually underestimate her. Evans’ acting is intentionally at odds with the other characters, a twenty-first-century woman stuck in a world with the masculine ideals of the nineteenth.

The most unusual character in the play, besides Nora, is Michael J. Asberry as Dr. Rank. In the original work, Dr. Rank is a dour, hopeless character, doomed both to a one-way infatuation with Nora and a painful terminal illness. However, Asberry’s poise and charisma lend the fatalistic doctor the bearing of a king, as he towers over the others in stage presence as well as height. Dr. Rank’s philosophy and motivations run perpendicular to the dignity-focused society of the play, but Shotgun’s production, backed by Asberry’s performance, asks if perhaps he was closer to the truth than the others suspected.

The other men of the play are not given such flattering treatment: Nora’s husband Torvald (Kevin Kemp) is a swaggering, condescending brute from his first line, and Krogstad (Adam Elder) is as much a villain as he was in the original text. These interpretations reflect director Beth Wilmurt’s commentary on both Ibsen’s work and modern toxic masculinity, and would be heavy handed in a more character-focused version of the play. However, in this production, which takes a more introspective, symbolic view of Nora’s struggles, these characterizations smoothly fit the broader tone. Erin Mei-Ling Stuart periodically drifts onstage as Mrs. Linde, Nora’s wife and closest ally. Though her life is difficult, Mrs. Linde is hardened enough to bear it, and is able to help Nora through her journey without pushing her. Stuart’s interpretation feels more like a force of nature than a person – a comforting breeze when needed, and a thundercrack when called for.

The technical work (Maya Linke as set designer, Maggie Whitaker as lighting designer, Matt Stines as sound designer) creates a sense of intense pressure as Nora’s marriage to Torvald becomes more and more unbearable. Dark ambient noise interrupts the usual theatre silence, never allowing the audience to relax; the bare, minimalistic set leaves no place for the eye to wander. However, the most interesting twist is the upstage wall, wallpapered with women’s faces and bearing a set of double doors that lead to Torvald’s office. The wall clearly delineates Torvald’s life from Nora’s, the man’s sphere from the woman’s, pushing slowly forward over the course of the show until only a few feet remain for the female characters to stand. It’s a brilliant work of nonverbal poetry that ties together the larger themes of the show.

Nora at Shotgun Players explores new meaning in a text familiar to theatre veterans, yet still presents a coherent story for newcomers. The themes and characters from the original are adapted to fit a modern context and the director’s vision, but not so much to be unrecognizable. While the base text is a Swedish play written over a century ago, Nora – and innovative companies like Shotgun – represent the future of American theatre.