A note from Managing Director Liz Hitchcock Lisle

Liz Hitchcock Lisle

Shotgun Players Managing Director Liz Lisle says, “Shotgun has become known as a company that puts on plays that investigate the human condition, and that can mean a lot of different things. Sometimes our moments of reckoning are pretty extreme—considerations of life and death, tragedy and survival. But that's not the only way life happens, and it's certainly not the only place where really profound and interesting human interactions occur.

In this building, we consider it our job to tell stories about people that don't traditionally get a spotlight. The Flick is this incredible play in that it allows us a chance to spend time with a group of people who don't get regular consideration—movie theater employees. There are no earthquakes in this play, and nobody dies. But the interactions these characters have, and how they proceed through time is riveting—if you give yourself over to it.

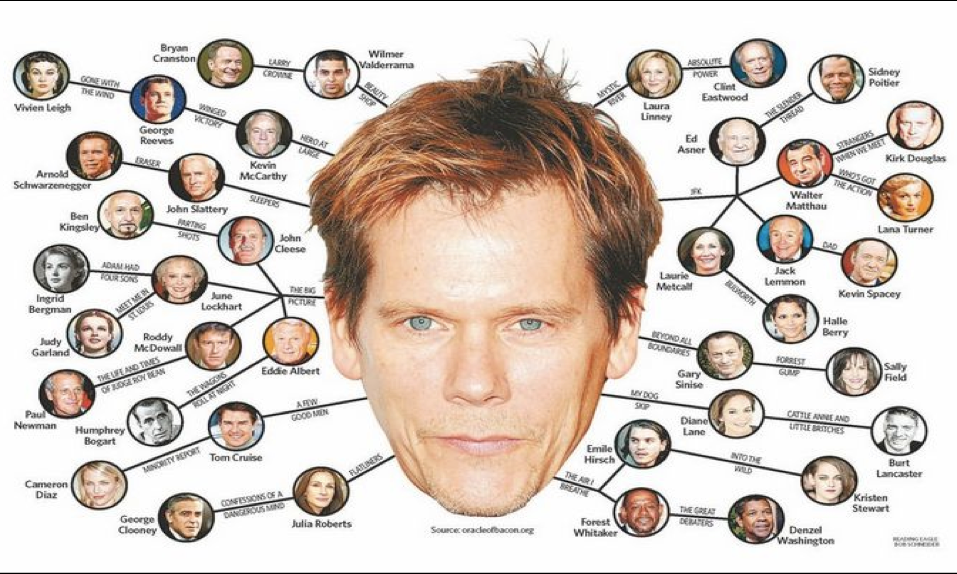

Six degrees of Kevin Bacon

Six degrees of Kevin Bacon | Source: markrobinsonwrites.com

This is a popular game that movie buffs play. It’s pop culture take on the concept, “six degrees of separation.” The concept posits that everyone on Earth is six or fewer acquaintances apart from each other. In this game, movie aficionados challenge each other to find the shortest path between an arbitrary actor and prolific actor Kevin Bacon. It rests on the assumption that anyone involved in the Hollywood film industry can be linked through their film roles to Kevin Bacon within six steps.

In The Flick, characters Sam and Avery play a variation of this game, as they connect two actors or artists of their choosing:

Sam: Jack Nicholson and Dakota Fanning.

Avery: That’s too easy.

Sam: Well just do it then.

Avery: ...Jack Nicholson to Tom Cruise in A Few Good Men. Tom Cruise to Dakota Fanning in War of the Worlds.

Come up with a better one.

Give it a go yourself and see if you can connect two actors either to Kevin Bacon or to each other!

Here’s a starter one:

Brad Pitt to Bette Midler

Director Jon Tracy writes of his experience reading The Flick

Jon Tracy | Photo by Robbie Sweeny

I finished The Flick. Closed the script. Was asked, "what were you reading?"

“A book of poems about folks I know.”

I grew up in a small city that felt like the entire world. I wasn't given any great tools to navigate communicating with others so I communicated through trivialities while jockeying for a place in it all, any place. Inside, everything burned hot. Outside I begged silently for a chance to really trust someone and continued to lower my standards in hopes of attaining some semblance of friendship. My memories of “epic moments” from my teens and twenties are so small in the greater scheme of things: that time she laughed at my joke or anything that felt like camaraderie for even a split-second.

But they are my epic moments. And they shaped me. Each of them drag me down while also make me long for the certain beauty of those times. To reconstruct them seems unimaginable. To make them present seems impossible. But The Flick did it through the construction of poems that together speak for a longing to connect through an inner music never played but, because of how technically the play puts it all together, a music we all remember. Perhaps an inner music that continues to burn hot.

Annie Baker and the action of silence

Annie Baker | Source: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Perhaps one of the reasons The Flick received the 2014 Pulitzer Prize is that Annie Baker crafts not only the dialogue but also the exquisite moments of silence with her play. Here are some examples of her stage directions:

“Sam gets weird”

“A very long, uncomfortable pause”

“Another weird pause”

“A happy pause in which they realize they’ve broken the tension, and then awkward pause following the happy pause.”

In an NPR interview with Robert Siegel, Annie Baker responded to the question of her use of pauses with The Flick:

You know, it's very instinct driven and I didn't even really think of myself as a person who wrote a lot of pauses and silences into my play. For me, it was just actually sort of transcribing and recording the scene unfolding in my mind onto the paper. But time is something and duration was something I was particularly interested in addressing in The Flick, both through the length of the play, which is over three hours and just the way I feel like that’s going back to just sort of the relationship between theater and film. I think theater is so special because time is passing at the same rate for the actors on stage as it is for the audience, which is completely different than film and TV and other mediums. And I also think time works differently with celluloid than it does with the digital image and that contrast between mediums and the way you experience time through them was something I really wanted to deal with in The Flick.

Director Jon Tracy adds:

The Flick answers that great question: what happens when the lights come up? After the curated spectacle of a film or, in our lives, the theater, the lights come up and LIFE happens. And it's that LIFE, that I'm interested in uncovering… Annie Baker doesn't just give us those few moments after the lights come up because those moments are easy for us to attain now. No, she makes us sit with it: knowing that so much of our lives are the hours between. So many stories are about survival. This one is too but it is about a section of survival rarely amplified: maintenance. How we repair between events.And because it is all of the above, it also becomes hysterical and devastating at the same time.