"Scintillating... engrossing theater."

"Scintillating... engrossing theater."

- Robert Hurwitt, SF Chronicle

"Positively world class... a persistent joy... the playwright's brilliance lies precisely in his ability to wed such weighty subject matter to a playful, generously humorous brand of madcap dialogue and witty wordplay that even someone who flunked out of philsophy class can enjoy."

- Alex Bigman, East Bay Express

"Shipwreck is a stunning dramatic achievement for this small company whose artistic standards remain 'as high as an elephant's eye.'"

- George Heymont, My Cultural Landscape

"An impressive production... visually spectacular."

- Matthew Murray, Talkin' Broadway

____________________________________________

Shipwreck Review: Engrossing Journey

Robert Hurwitt

Sunday, March 31st

San Francisco Chronicle

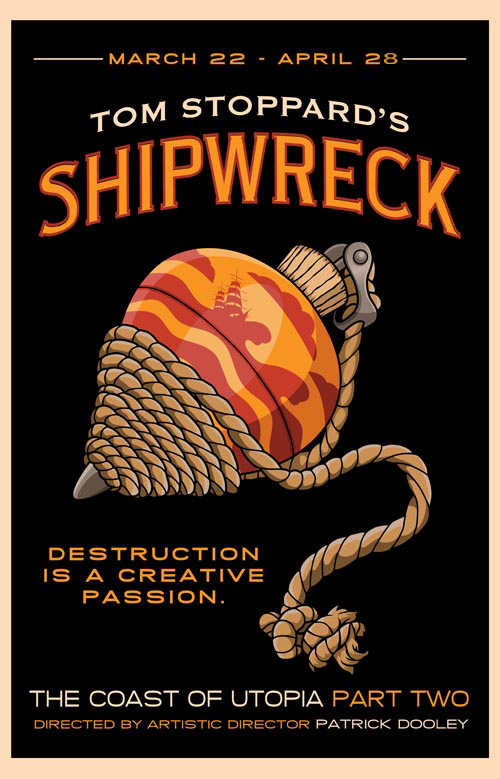

Love proves a complicated thing for the 19th century Russian revolutionaries in "Shipwreck," the second part of Tom Stoppard's scintillating "The Coast of Utopia" trilogy. Actual revolutions prove even more disheartening for the characters in the ambitious Shotgun Players production that opened Friday. That's why Stoppard called the second installment "Shipwreck."

It's a fascinating tale, as Stoppard interweaves family lives with the evolution of different strands of progressive thought in the mid-19th century. He does this not only in politics - though pitting the great early socialist Alexander Herzen against Karl Marx and proto-anarchist Michael Bakunin might seem enough for any one play - but in literature, love, painting and sexual freedom as well.

Theory, tested and shaped by the heat of unfolding events, makes for engrossing theater, despite some uneven passages in director Patrick Dooley's production. "Shipwreck" can stand alone, but it offers more to those who've experienced "Utopia" part one, "Voyage," which Shotgun staged last year. Newcomers with stamina may want to take advantage of the revived "Voyage" in Saturday matinees before an evening of "Shipwreck."

The second part profits from a tighter focus. Where "Voyage" spanned 11 years, starting in 1833, on the Bakunin family country estate and in Moscow, "Shipwreck" takes place in 1846-52, mostly in Paris and Nice (then part of the Italian kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia). Though Joseph Salazar's dashingly intense Bakunin still plays an important role, his serial embrace of radical philosophies now takes a backseat to developments in the Herzen household - and the fallout from the failed revolutions of 1848.

Patrick Kelly Jones' thoughtful, committed and gentlemanly Herzen provides the ever-more-critical focal point for all the events swirling around him. His reactions to the unfolding rebellions and setbacks of '48 (the timetable in the program is very helpful) register as strongly on an emotional as intellectual level, bolstered by the graphic accounts of Ivan Turgenev (a somewhat too mannered Richard Reinholdt) and the competing ideas of Dan Saski's self-absorbed young Marx, Bakunin, the Slavophile Aksakov (Ben Landmesser) and others.

Bakunin and like-minded cohorts dash off to join revolutions in Poland and German states, with some provocatively sardonic comic touches. Meanwhile, Nick Medina's sickly, fervid literary critic Belinsky notes the fall of Gogol and rise of the talents of Turgenev and Dostoevsky, while the intersection of social and sexual revolutions may prompt 1960s-Berkeley flashbacks in older members of the audience.

Love gradually takes center stage as the proving ground for ideas of freedom. Herzen faces it first in his best friend, Sam Misner's sadly radiant poet Ogarev, steadfast in his fidelity to his wife, Maria (a sensually pragmatic Christy Crowley), who's long since left him for a French painter. Then it invades his household, testing his smart, questing wife Natalie's devotion to ideals drawn from George Sand when they share a house with German love-icon poet George Herwegh (a delightful Daniel Petzold) and his devoted, neglected wife, Emma (the magnetic Danielle O'Hare).

As Natalie, Caitlyn Louchard's expressive features and earnest pronouncements anchor the emotional story, bouncing off Jones' internal struggles and the passions of O'Hare, Petzold and Crowley. A seductive tableau of Manet's "Le déjeuner sur l'herbe" could be the most attention-grabbing scene, but it's the Herzens' riveting marital showdown that delivers the dramatic and thematic crux. Whatever the production's failings in some roles and scenes, its success here whets the appetite for the trilogy's conclusion with "Salvage" next year.

A Stimulating Shipwreck

Alex Bigman

Wednesday, April 3rd

East Bay Express

Coast of Utopia, Tom Stoppard's 2002 trilogy of plays, was destined to be either the playwright's crowning masterpiece or late-career folly. The general consensus seems to be that it is both. Totaling more than seven hours and involving several dozen characters, it's also a fairly herculean undertaking for a small company like Shotgun Players.

The company decided to stretch the trilogy over three years, performing part one, Voyage, last year, part two, Shipwreck, presently, and part three, Salvage, in 2014 (assuming all goes according to plan). It's a fairly awkward arrangement, given the difficulty of getting a cast of more than thirty to commit to something so far down the road. Then there's the fact that some viewers are bound to enter this very complex narrative midway through and won't have the stamina for back-to-back viewings, which the company has encouraged by offering a few matinee re-stagings of Voyage. So they better believe that Shipwreck can stand up on its own.

It can and it does. Having not seen Voyage, I was admittedly lost for a good portion of Shipwreck. But that didn't stop me from falling head over heels for the play just the same.

Voyage, which begins in 1830s Russia, introduced the character of Michael Bakunin as an idealistic university student, who makes friends with the set of young intellectuals (including poet Nicholas Ogarev, "father of modern socialism" Alexander Herzen, and famed author Ivan Turgenev). Shipwreck picks up in 1848, the year that a wave of revolutions shook up Europe — notably France. The friends, now in their thirties, have made it West for the excitement.

At this juncture, Bakunin (Joseph Salazar) is busy with the revolutionary freelancing that will eventually earn him the title "Father of Anarchism," and the play shifts focus to Herzen (Patrick Kelly Jones), who has married a woman named Natalie (Caitlyn Louchard) and has a deaf son named Kolya (Sebastian Mora). The gang is busy brushing elbows with the likes of Karl Marx and Richard Wagner and developing their great political theories and literary works, while also negotiating their transitions into adulthood and a new class of Russian intelligentsia.

Shipwreck is also supposed to be the most love-struck and lovelorn chapter in the trilogy, dwelling as much on romantic politics as national ones. As with most close friend groups, this one is delightfully incestuous, with betrayals, reconciliations, and love triangles — in particular an affair between Natalie and the rebel German poet Georg Herwegh (Daniel Petzold). Missing Voyage makes for some inevitable confusion in this romantic domain, where complex personal histories pick up where they left off without stopping for a moment's recapitulation. For example, the character of Maria Ogarev (Christy Crowley), Nicholas' seductive and unfaithful wife, takes the play from zero to soap opera in seconds flat with her one scantily (un)clad appearance, in which she cattily attacks Natalie. The suddenness of Natalie's subsequent liaison with Georg is an equally disorienting jolt, all the more so considering its bizarre mise-en-scène: an enactment of Édouard Manet's "Luncheon on the Grass." But it is just this kind of zany maneuver that makes Shipwreck such a persistent joy in spite of the occasional moment of bewilderment.

Ultimately, the success of Stoppard's wildly ambitious work depends on the company that produces it, with the foremost challenge being to draw a unique and beguiling personality out of each character while also setting a group dynamic in motion. Shotgun Players' production, directed by Artistic Director Patrick Dooley, is positively world class in this regard. The cast is uniformly strong, making for distinctive characters that convene, disperse, and reconvene in innumerable formations on an often very crowded stage, expounding their lofty arguments and assuming their absurd art-historical tableaux, forming an inter-human lattice that is absolutely greater than the sum of its parts.

Some viewers may experience exhaustion from the play's breathless pacing and the playwright's pronounced voice. I, for one, emerged hopelessly invested in this group of fictional friends and the players that brought them to life. So, I bear up for what is bound to be one of the most agonizingly long intervals between serial installments ever, counting down the days until part three.

My Cultural Landscape

George Heymont

Wednesday, April 3rd

To be honest, I wasn't sure this was going to happen. Last year, when Patrick Dooley directed Voyage (the first part of Stoppard's trilogy), I found it difficult to follow the convoluted unraveling of a play in which numerous characters jump back and forth in time over a period of nearly 50 years. This month, Shotgun Players will be performing Voyage on several Saturday matinees prior to evening performance of Shipwreck. Next season, Dooley anticipates staging the the final installment, Salvage, as well as the entire trilogy at the tiny Ashby Stage (a converted church in Berkeley which is run entirely on green energy and barely seats 150 people).

Because Shipwreck follows a chronological unraveling of events running from the summer of 1846 until August 1852 (with a final, heart-rending flashback), it's much easier to understand. And, because much less time is spent debating radical philosophies (and greater attention is focused on personal relationships, marital stress, a child's disability, and the crushing pain of unrequited love), the story becomes far more accessible to audiences.

Considering that both plays use the same set designer (Nina Ball), costume designer (Alexae Visel), shared many of the same actors, and were staged by Dooley (who is the artistic director of Shotgun Players), what made Shipwreck so much more enjoyable? At its core, Stoppard's play also has a deeper sense of poetry and humanity (the kind which can elevate a soliloquy into a rarefied moment of theatrical artistry and yet melt an audience's heart with the look on an inquisitive but wordless child's face).

At the center of the play are Alexandre (Patrick Kelly Jones) and Natalie Herzen (Caitlyn Louchard), illegitimate children of a Russian nobleman. Upon his father's death, Alexandre inherited an unimaginable fortune. After marrying his first cousin, they had two sons. The older boy, Sasha (Jonah Rotenberg) is a normal child; the younger one, Kolya (Sebastian Mora) is deaf but shows remarkable signs of comprehension.

After Herzen receives permission to travel to Europe in search of medical care for Kolya, he arrives in Paris with his family in late 1847 just as the citizens of France (considered Europe's center of change) vote to revert back to a monarchy. Among his idealistic friends who have left Russia and moved to Paris are Ivan Turgenev (Richard Reinholdt), Karl Marx (Dan Saski), Vissarion Belinsky (Nick Medina), Natasha Tuchkov (Megan Trout), and Ogarev's first wife, Maria (Christy Crowley) who is now living with the painter Leonty Ibayev (John Mercer).

As time moves on, the dedicated revolutionary, Michael Bakunin (Joseph Salazar), befriends composer Richard Wagner and Herzen's wife, Natalie, falls under the spell of the German poet, George Herwegh (Daniel Petzold), who can't see to stay interested in his own wife, Emma (Danielle O'Hare). Meanwhile, Kolya's grandmother, Madam Haag (Monica Cappuccini), is helping the boy to learn how to read lips. When orders come for Herzen to return to Russia, he refuses to go.

I tip my hat to Patrick Dooley for the constant ambitiousness of his artistic vision, the skill with which he has directed a large cast without ever losing sight of how to craft moments of great intimacy onstage, and the results he has pulled from a magnificently

talented ensemble that features actors from multiple generations. Even more than last year's production of Voyage, Shipwreck is a stunning dramatic achievement for this small company whose artistic standards remain "as high as an elephant's eye".

An Engaging Production of Tom Stoppard's Shipwreck

Richard Connema

Sunday, April 7th

Talkin' Broadway

Last year, Shotgun Players stepped up to the plate and presented a splendid production of Part 1: Voyage of Tom Stoppard's historical drama Coast of Utopia. This season the company is presenting an impressive production of Part 2: Shipwreck. There will be six performances of Voyage on Saturday matinees with Shipwreck to follow in the evenings.

Shipwreck takes off from Voyage with the crowded opening scene of young Russian radicals during the summer of 1846 arguing political philosophy in the gardens of Sokolovo estates just outside Moscow. They are "superfluous" men whose education, upbringing and talents make them a threat, not an asset, to their country. They look forward to a future of idleness. The intelligent group cannot travel and they have no need to work; they even argue about coffee. The audience hears the downhearted reflections of Ivan Turgenev (Richard Reinholdt) and the tormented monologues of Alexander Herzen (Patrick Kelley Jones). The production then carries the audience through the Paris student revolutions of 1840 and aftermath. Intermingled with the spectacles the audience also gets a chance to see their private lives, and their marriage and infidelity problems.

Staged with energy and fluidity, with more than 20 actors under the robust direction of Patrick Dooley, Shipwreck is as visually spectacular as Voyage, thanks to Nina Ball's free flowing set of white drapes covering the intimate stage. This is certainly the most theatrical evening of the season thus far. There are many unforgettable scenes, such as the Place de la Concorde before, during and after the 1848 revolutions. Many of the speeches are eloquent and the playwright enlivens some scenes with his playful wit. There are many quarrels among Herzen and his philosophical comrades that sometimes devolve into comic disagreements.

Patrick Kelly Jones gives a brilliant performance as Alexander Herzen, the play's central figure. His speech at the end of the production is powerful. Caitlyn Louchard is marvelous as Herzen's romantic and emotionally needy wife Natalie. Richard Reinholdt gives a charismatic presentation of the seemingly detached artist and writer Ivan Turgenev, who wrote the pre-Chekov classic play A Month in the Country. Joseph Salazar does a compelling portrayal of the son Michael who has just returned from France with talk of revolution. This quartet is responsible for extraordinarily harmonic creations that manage to remain separate and individual even as they blend into a whole.

Nick Medina once again is convincing as the critic Vissarion Belinsky who asserts he could write better in an expensive dressing grown he's spotted in a Paris shop. He retains the no-nonsense intelligence and youthful zeal of the role. Daniel Petzold stands out as famous rebel poet German poet George Herwegh, Herzen's friend and eventual rival. Christy Crowley shines with sensuality as the realistic Maria Ogarev in the second act while Monica Cappuccini is perfect as Madam Haag in a small but showy role.

Dan Saski gives a very good performance as the egocentric young Karl Marx while Ben Landmesser is compelling as Aksakov. Danielle O'Hare gives a magnetic performance as Emma the wife of love-icon poet George Herwegh.

Joe Lucas, John Mercer, Sam Misner, Nesbyth Rieman, Alex Shafer, Leanna Sharp, Sam Tillis, Kenny Toll and Don Wood are all first rate and give life and vivacity to a script that could easily get mired in sociopolitical mud. Five-year-old Sebastian Mora (alternating with Nathan Weltzien) as Kolya and 12-year-old Jonah Rottenberg (alternating with Kachi Gauthier) as Sasha are appealing in the production. This is a journey no lover of serious theatre should miss.