the music of sunday in the park with george

“Color and Light”

“It’s Hot Up Here”

“Sunday”

Writer James Lapine and Composer & Lyricist Stephen Sondheim

How Sondheim and Lapine Made a Masterpiece

“When I first hear a song sung, I’m worried that I’m going to be embarrassed by what I wrote,” said Stephen Sondheim while Sunday in the Park with George was in previews. “So I try to postpone the moment.” The quote is endearing, and more than a little absurd, coming from the patron saint of musical theatre—but in early 1984, Sondheim hadn’t quite hit apotheosis. His previous musical, Merrily We Roll Along, had closed on Broadway after a 16-performance run.

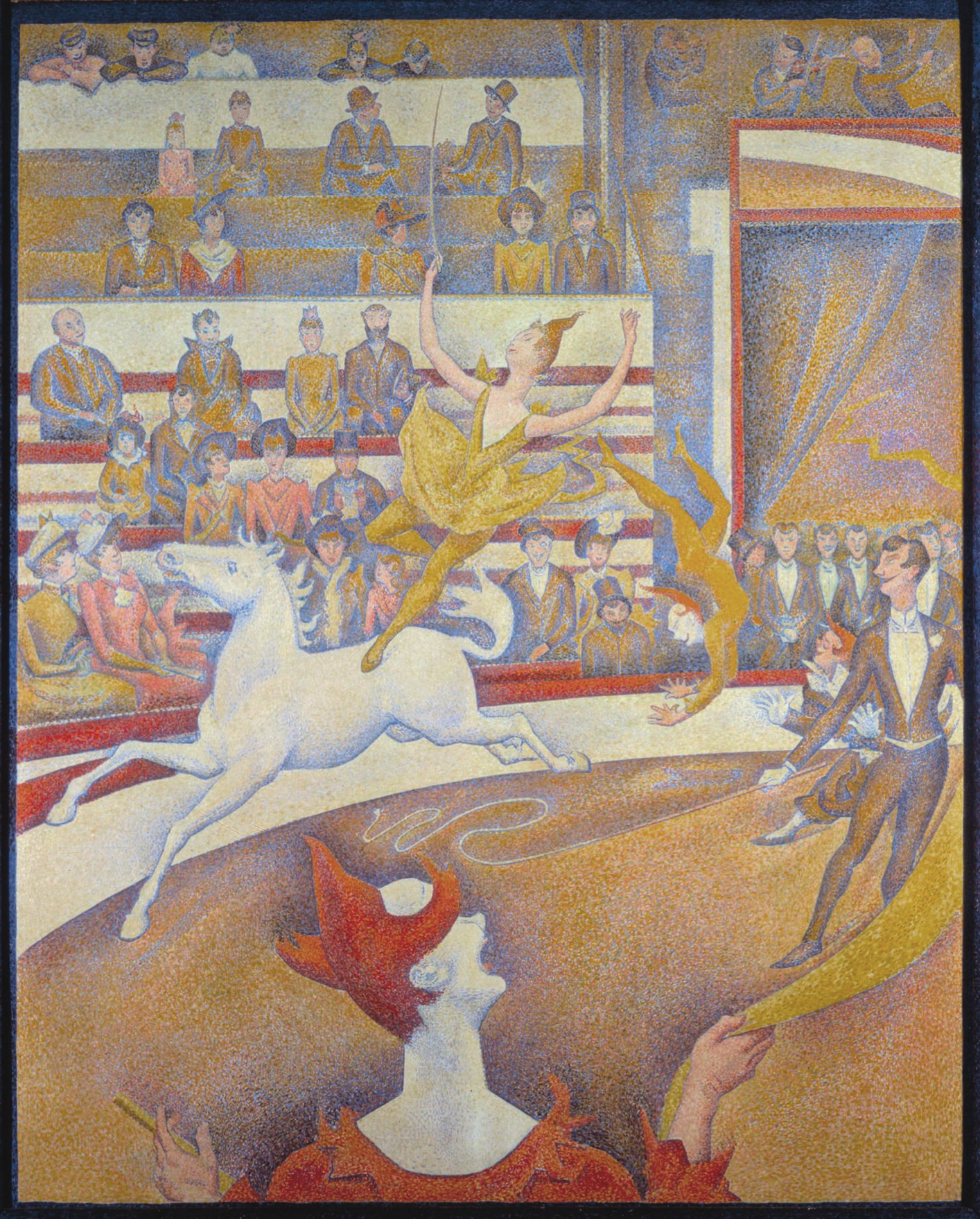

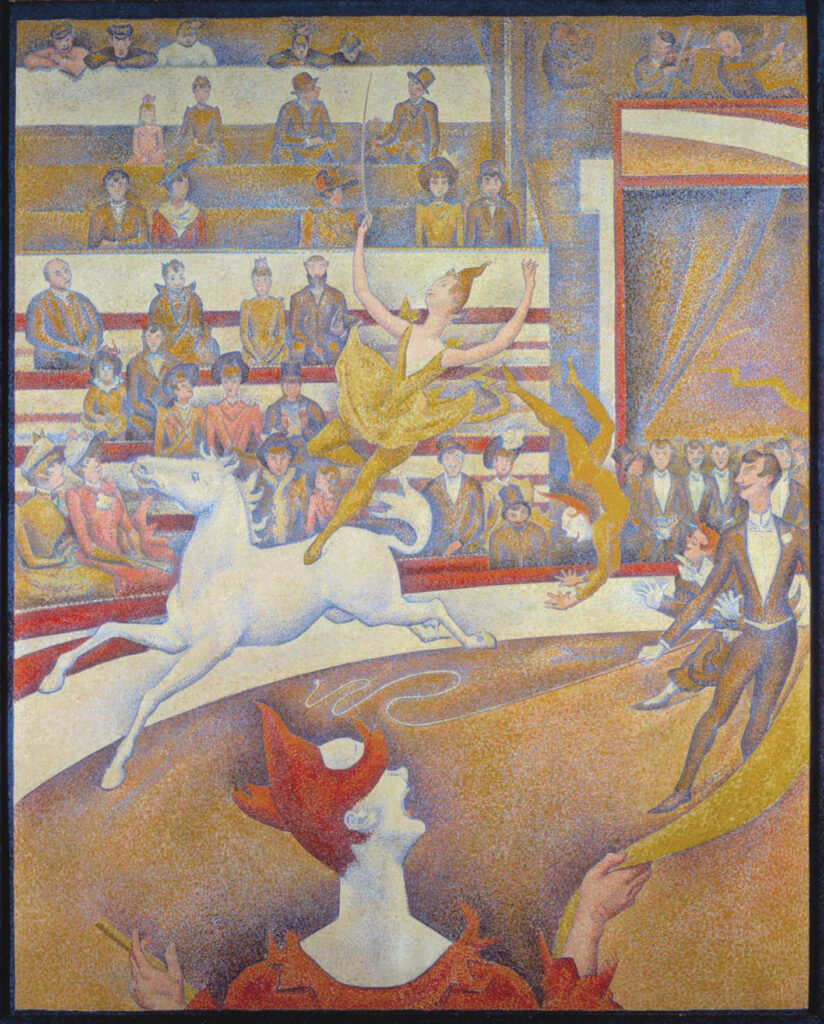

Then salvation came—in the form of a Pointillist masterpiece. In June 1982, Sondheim began a tentative collaboration with James Lapine, a young Off-Broadway playwright. In search of a subject, they began rifling through photographs and paintings, one of which was Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

The 1884 painting looked like a stage set, Lapine observed, but was missing the main character. “Who?” asked Sondheim. “The artist,” said Lapine. He laid tracing paper over La Grande Jatte and drew a constellation of arrows, each one pointing to an anonymous figure on the riverbank. “Mother?” he wrote. “Mistress? Butler?” It was like an existential game of Clue, a whodunit in which the answer was Georges Seurat.

The Broadway production opened May 2, 1984, and although it received a few positive reviews—as well as the Pulitzer Prize for Drama—the show was mostly met with bewilderment and hostility. Preview audiences walked out in droves, the Daily Newswrote that the musical “doesn’t bear looking at or listening to for very long,” and the second act was so polarizing that The Wall Street Journal suggested it be scrapped altogether. (Sondheim’s response: “Without the second half, the show’s a stunt.”)

The New York Times’ Frank Rich was virtually alone in giving the show a rave. “Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine demand that an audience radically change its whole way of looking at the Broadway musical,” he wrote.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

In the 1986 movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Cameron finds himself in a moment of serious introspection in front of Seurat’s painting.

The camera cuts back and forth between Cameron’s face and the face of the young girl at the center of the pointillist painting. Inching closer to the canvas with each cut, the camera is eventually so close to her face that it is no longer identifiable as such.

“He’s struggling to find his place and he dives into the face of that little kid,” says Harvey. “It almost brings me to tears, because he’s having a soul-wrenching, life changing experience. When he comes out of that painting, he will not be the same.” – Eleanor Harvey, Senior Curator, Smithsonian Museum

the directors

This Sondheim classic, an unconventional love story that imagines the interior life of French painter Georges Seurat, is helmed by Susannah Martin and David Möschler, the architects of our wildly successful Assassins (2012).

props & Chromolume design by SYDNEY PARCELL

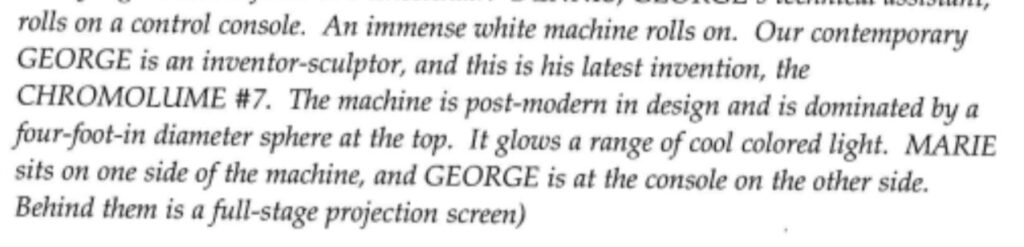

In my art practice, I explore optical illusions and viewer perception with light, shadow, and movement. I like to create things that highlight the hidden magic of the world around us. In reading the libretto and other papers on the Chromolume (link), I was fascinated about how this musical hints at the science and perception of color and light. I wanted the Chromolume to be able to demonstrate the essence of what both George’s are trying to communicate – how freaking cool the science of color and light is!!

I’d like viewers to notice that no direct white light is used in the Chromolume. With the use of directed light and shadows, the Chromolume demonstrates how colored beams of light are used to create different colors individually, and white all together. When the Chromolume projects light onto the floor, one can see the pointillism that makes up white light – Red, Green, and Blue light, and their respective mixed colors, Yellow, Cyan, and Magenta. Through the quick movement of these colors, our eyes can perceive white light, and also see the individual colors in your vision, much like in the painting.

Act Two: One Hundred Years Later

Writer James Lapine wondered why no one in the painting is looking at anyone else. He also noticed that the central character is missing: the painter. Those two observations were enough to jumpstart the creation of a musical about the (completely fictional) events leading up to the creation of this painting. Why aren’t the people in the painting looking at each other? Why is the woman in front placed so prominently? Sondheim and Lapine’s answer was that she was Seurat’s mistress, Dot, and the show became about George’s struggle (and the struggle of all serious artists) to reconcile his obsessive passion for his art with his often ignored personal life, represented by Dot.

In Act II, Seurat’s great-grandson, also named George, is in the midst of a personal and artistic crisis of his own, facing the same issues as his ancestor. There are two Georges and yet they are the same George. In Act 1, Dot sings:

And there are Louis’s. And there are Georges— Well, Louis’s… And George.

Though most of us are not one of a kind, George is; so much so, that even when there are two of them, separated by a hundred years, they are really the same man.

The same ensemble of actors appears in both acts, each playing different but often parallel roles. The actor who plays George in Act I also plays the 1980s George in Act II. The actor who plays Dot reappears as her daughter Marie, George’s grandmother. Seurat’s mother becomes an art critic and friend to the modern George. Jules, Seurat’s rival and the more conventional, commercially successful painter, returns as the museum director, still walking the line between making art and making a living. The crass, uncultured American from Act I reemerges as a crass but well-funded art patron in Act II.

Read the full article at New Line Theatre.

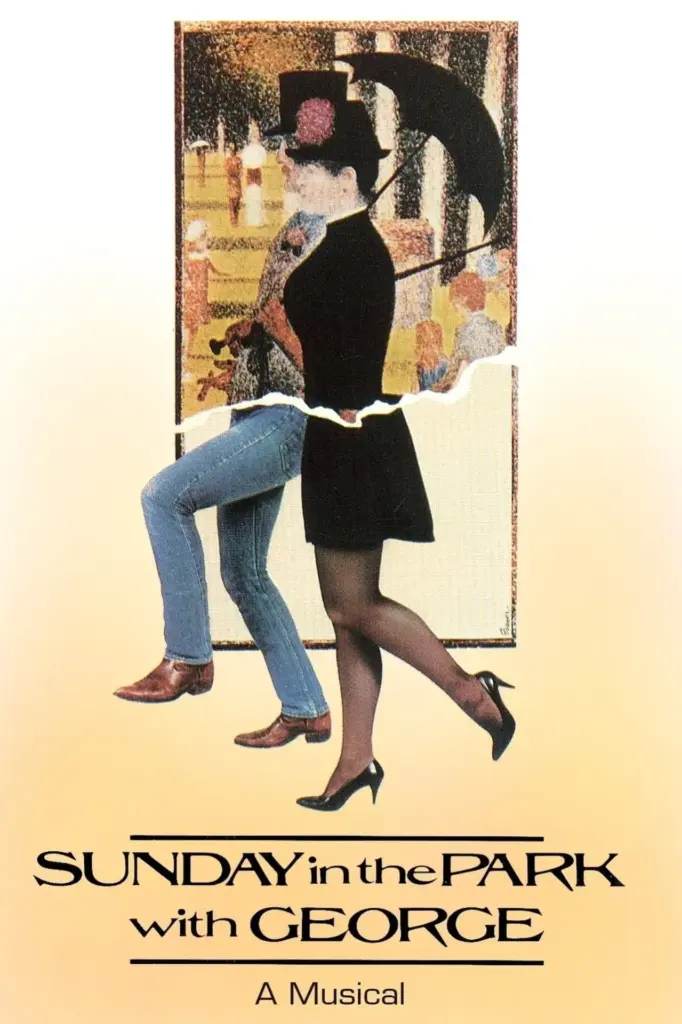

Poster art from the original production, showing Seurat’s Paris of 1884 fading into the modern artist’s search for meaning a century later.

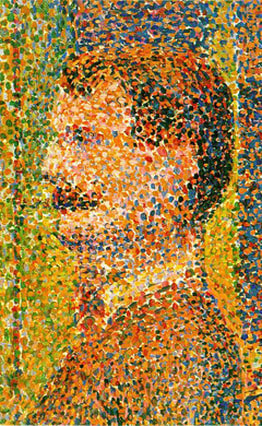

the art of GEORGES SEURAT

“George has many secrets…”

In 1889, 3 years after exhibiting La Grande Jatte, Seurat began living with Madeleine Knobloch, his 21 year old lover. On February 16, 1890, Madeleine revealed to him his son, whom he officially acknowledged and entered in the register of births under the name of Pierre-Georges Seurat. Despite having painted Madeleine in Young Woman Powdering Herself in 1889-90, he continued to conceal her and their relationship from even his closest friends and family. The day following his death, Madeleine presented herself at the town hall to identify herself as the mother of Pierre-Georges Seurat. Their child died of the same condition as his father shortly after, on April 13, 1891.

“Whenever we have knowledge of those [living] circumstances, we learn that there is a dialogue between model and image. In Seurat’s case, we know that his image is based on a professional model who was also his lover (her generous size may owe something to her pregnancy). We are bound to wonder at Seurat’s using her as the model for a picture that elevates her to iconic power while also making of her an ironic image of life’s vanities” – Robert L. Herbert

– Dramaturgy by Bella Campos Hintzman

Georges Seurat, Une baignade à Asnières (Bathers at Asnières) · 1887–88

“George taught me all about concentration…

The art of being still“

“Several men and boys relax on the banks of the Seine at Asnières and Courbevoie, an industrial suburb north-west of central Paris. Shown in profile, they are as immobile as sculptures and each seems absorbed in his own thoughts, neither engaging with each other nor with us. Suffused with bright but hazy sunlight, the entire scene has an almost eerie stillness to it, as if time has been suspended and all movement temporarily frozen.” – The National Gallery

“how George looks. He could look forever. As if he sees you and he doesn’t, all at once…”

“Toulouse-Lautrec would have seized at once on all that was significant of the moral atmosphere, would have seized most of all on what satisfied his slightly morbid relish of depravity… But Seurat, one feels, saw it almost as one might suppose some visitant from another planet would have done. He saw it with this penetrating exactness of a gaze vacant of all direct understanding… Each figure seems to be so perfectly enclosed within its simplified contour, for, however precise and detailed Seurat is, his passion for geometricizing never deserts him… The syntax of actual life has been broken up and replaced by Seurat’s own peculiar syntax with all its strange, remote and unforeseen implications.” – Roger Fry

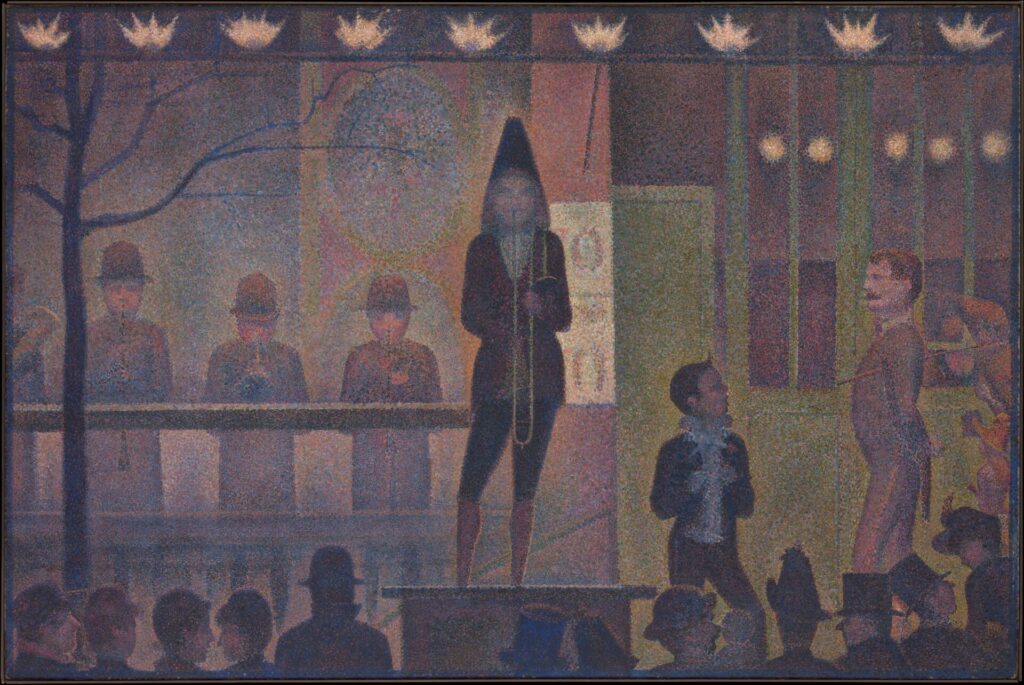

Georges Seurat, Parade de cirque (Circus Sideshow) · 1887–88

“Nobody can even see my profile”

The figure of the nurse, who appears frequently in Seurat’s drawings is recognizable by her bonnet with long ribbons in the back, the attribute of the Parisian wet nurse of the second half of the nineteenth century. Wet nurses played a major role in Parisian social life of the time and were a common sight in the city’s public parks. – The Morgan Library & Museum

Matt Standley as the Boatman

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (detail), 1884–86

The Chromolume “light sculpture” from the original 1984 Broadway production

1980’s Art and Culture in the United States

“Seurat was a respected artist who happened to be a commercial failure in his lifetime. We decided that contemporary George should be just the opposite: commercially successful but at a crossroads where he’s lost touch with his artistic vision” – James Lapine

George of Act 2 is an inventor-sculptor living in 1984. His “Chromolume #7” embraces lighting design and technological innovation (both in the world of the show, as well as in the show’s production history beginning with the original Broadway production). The art scene of the 1980’s in the United States can be characterized by a divergence from minimalism, artists challenging traditional gallery spaces, and a rise in popularity of mixed media, installation art, performance art and photography. Sculpture particularly expanded in form to include interactive experiences, further broadening the possibilities and modalities of what art could be.

– Dramaturgy by Bella Campos Hintzman

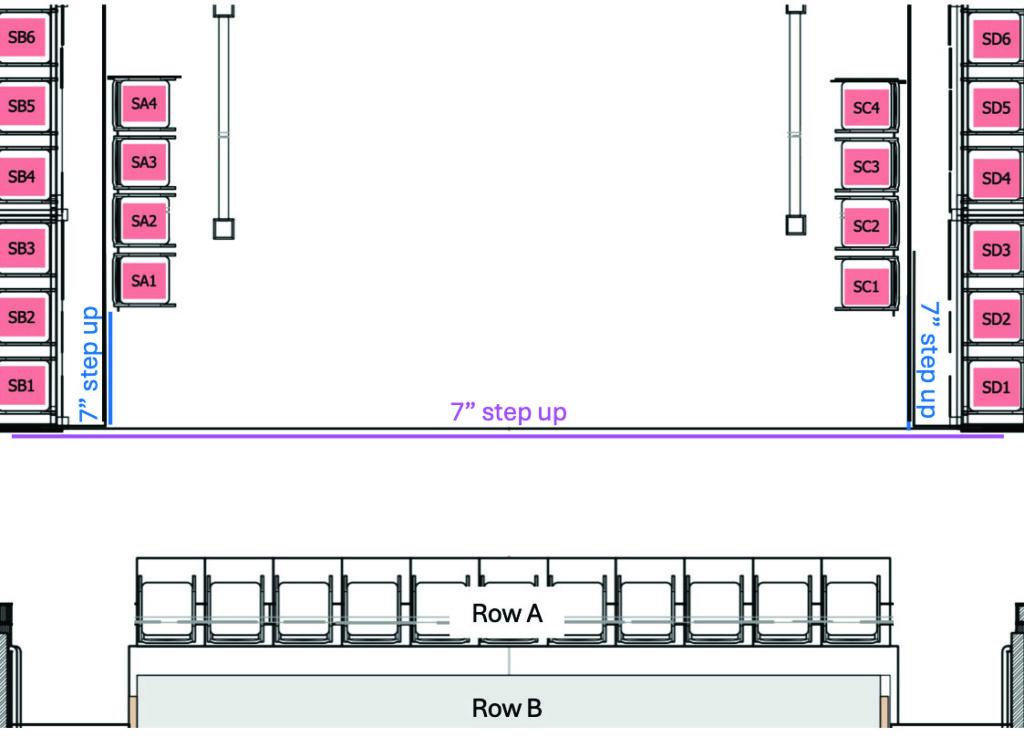

the onstage seating experience

Ever wonder what it’s like inside a painting? Sit onstage and find out. Step into George Seurat’s masterpiece, on the Isle of La Grande Jatte, where you may even find yourself a part of the picture.